Stephen Halpert Marriage and Family Therapy Berkeley Ca

Effectiveness of Structural–Strategic Family Therapy in the Treatment of Adolescents with Mental Health Issues and Their Families

1

Faculty of Psychology, University of Seville, Camilo José Cela southward/n, 41018 Seville, Spain

2

Kid and Adolescent Mental Wellness Unit, Virgen Macarena Hospital, C/ Dr. Fedriani, 3, 41009 Seville, Spain

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

†

Deceased 13 September 2017.

Received: viii March 2019 / Revised: 1 April 2019 / Accepted: iv April 2019 / Published: 8 Apr 2019

Abstract

Mental health issues during adolescence constitute a major public health concern today for both families and stakeholders. Accordingly, unlike family-based interventions have emerged as an effective handling for adolescents with certain disorders. Specifically, there is testify of the effectiveness of concrete approaches of systemic family therapy on the symptoms of adolescents and family unit performance in general. All the same, few studies have examined the effectiveness of other relevant approaches, such as structural and strategic family unit therapy, incorporating parent–child or parental dyadic measurement. The purpose of this study was to test the effectiveness of a structural–strategic family therapy with adolescents involved in mental health services and their families. For this purpose, 41 parents and adolescents who participated in this treatment were interviewed at pre-examination and postal service-test, providing information on adolescent behavior problems, parental sense of competence, parental practices, parenting brotherhood, and family unit functioning. Regardless of participants' gender, adolescents exhibited fewer internalizing and externalizing problems subsequently the treatment. Parents reported college family cohesion, higher satisfaction and perceived efficacy as a parent, and healthier parental practices (less authoritarian and permissive practices, as well as more authoritative ones). An interaction effect betwixt parenting alliance and gender was institute, with more favorable results for the mothers. In conclusion, this paper provides prove of the usefulness of structural–strategic family therapy for improving family, dyadic, and individual facets in families with adolescents exhibiting mental health problems.

1. Introduction

Mental health bug during adolescence constitute a major public health concern today for both families and stakeholders [one,2]. Epidemiological studies evidence that mental health issues are the outset nonfatal cause of illness [3], are in the peak five causes of death among adolescents [4], and represent 16% of the global wellness-related burden in immature people [4,5]. In addition, mental health problems during adolescence are an of import predictor of socialization difficulties and absenteeism at this developmental stage, every bit well as ane of the nigh meaning predictors of adjustment problems and mental disorders in adulthood [6,7,8]. In society to address these pressing issues, it is essential to have effective intervention and prevention strategies that meet the specific needs of adolescents with mental wellness problems.

Adolescence is a challenging transitional period for both children and families. It is a developmental stage characterized by normative physical, social, and psychological changes [9], some of which may be identified as potentially stressful among this population [x]. Psychosocial stress in adolescents can be accentuated past the presence of stressful or adverse life events (every bit maltreatment and violence, loss events, intrafamilial problems, school and interpersonal problems) that are associated with severe negative outcomes [eleven]. Although there are important inter-private differences, the electric current homogenization of adolescents' daily experiences has contributed to the observation of fewer cross-cultural and gender differences during this phase [12]. Some of the normative developmental tasks that adolescents need to undertake for a good for you development are the search for autonomy, identity, and independence [9]. For families, this is a menses characterized past the readjustment of family roles and norms, along with an increase in family conflicts [9,thirteen,14]. Families face the challenge of adjusting to these new demands and needs while trying to conserve family unity [9,13,fourteen]. The inability to adjust to these new demands, together with inflexibility within the family over the negotiation of new norms and different solutions, are often related to mental health problems. Families with an boyish with mental health problems take additional needs, demands, and difficulties stemming from the mental disorder [fifteen]. Parents frequently face challenging behaviors and conflictive situations, having to manage symptoms and coordinate and engage with different service systems [xvi,17]. Equally they struggle to deal with these additional demands, parents oft find their skills coming into question, and this can be accompanied by feelings of low competence, frustration, and powerlessness, together with increased isolation and contraction in their social network [15,eighteen].

At that place has been a proliferation of family-oriented and family unit-based interventions with adolescents with mental health difficulties; some of these are considered every bit evidence-based practices in the treatment of children and adolescents with certain disorders [19,20]. Previous enquiry indicates that the incorporation of family members or family elements in therapy is either directly or indirectly an constructive component of interventions that target adolescents with mental health problems [21,22,23]. On one hand, direct approaches (due east.g., family-centered behavioral management or family therapy) involve a more immediate engagement with the family and ordinarily include specific objectives that target families or family members. On the other hand, indirect approaches (e.g., psychodynamic therapy or cognitive–behavioral therapy) incorporate the family context through reviews or reports, using them as informants at some bespeak and by keeping the family unit elements in heed while intervening [22]. In sum, under the "family unit-based interventions" umbrella term, there are a broad range of qualitatively different interventions and approaches. The most widely used family-based interventions include psychoeducational approaches [24], behavioral interventions, and systemic family therapy [25]. The goal of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of specific systemic family therapy approaches in families with an adolescent presenting a mental health trouble.

From a systemic perspective, family is divers as a transactional system, where difficulties in whatever member have an influence on every other fellow member and on the whole family unit as a unit. In plough, family processes have an impact on every individual member, also as on the different relationships embedded within the family context [26]. This perspective shifts away from a linear consideration of family processes past recognizing the multiple recursive influences that shape family relationships and family operation, perceiving information technology as an ongoing procedure throughout the life cycle [27]. Systemic family therapy has been shown to be an efficacious intervention for families and adolescents with a broad range of mental health problems, such as drug use [nineteen,28,29,30,31,32]), eating disorders [29,thirty] and both internalizing and externalizing disorders [19,29,xxx,31,33,34,35,36]. Despite these advances, about of the literature has focused on either systemic family therapy every bit a whole, without taking into account the unlike approaches embedded within this framework, or on the effectiveness of more manualized approaches, such every bit multisystemic family therapy (east.chiliad., [37]) or functional family unit therapy (due east.g., [34,38]). Few studies have examined the effectiveness of more than classical and widely used approaches, such as structural and strategic family therapy [39]. Hence, more research is needed to be able to draw more definite conclusions regarding the use of these types of family therapy approaches.

Structural family therapy is one of the ascendant approaches in systemic family intervention, originally created by Minuchin [40]. The focus of this approach is on achieving a healthy hierarchical family organisation, where there are different subsystems with their limits and boundaries [27,41]. Co-ordinate to this approach, the difficulties expressed by the adolescent are a reflection of: (1) A family structural imbalance; (2) a dysfunctional hierarchy within the family system, ofttimes characterized by difficulties in establishing boundaries between the parental and the child subsystem; and (three) a maladaptive reaction to changing demands [27]. Therefore, the intervention focuses on reinforcing the parental subsystem, highlighting the need to present a "united front", and clearly differentiating it from the parent–child subsystem [25,27,41,42]. It also emphasizes the need to adjust the rigidity of the limits and the human relationship between subsystems according to the moment of the life cycle [42]. During adolescence, while authority still relies on the parental subsystem, the fashion it is exerted cannot be the same every bit in previous developmental stages, and the limits between the subsystems, while remaining clear, accept to be more flexible [25,27,42]. Although the cadre elements of this arroyo are well established and widely used among the clinical community [30,43], few studies have addressed the effectiveness of this approach for adolescents with mental health problems [39,44].

Strategic family therapy is purely embedded within the systemic model and has a more directive impression [25,45]. From this approach, the symptom is considered as serving a function to the family, as well as reflecting a difficulty of the family to solve a trouble [25,27,45]. According to the strategic approach, when faced with a problem, families adopt solutions that have been useful to them in the past. Withal, symptoms such as behavioral or emotional difficulties or an increase in conflicts emerge for which those solutions are no longer valid, and the family is unable to notice and effectively use alternative ones; thus, they become stuck in a symptom-maintaining sequence [27]. The objective of this therapy is for the family to initiate actions and solutions that are different to the ones previously attempted [27,45]. There is all-encompassing show well-nigh the effectiveness of the brief–strategic family unit therapy approach, which is a manualized and specific variant of the strategic approach, with different populations [46], including adolescents with mental health bug (e.g., [32,47,48]). Though structural and strategic family unit therapy are conceptually two different approaches within the systemic framework, they share certain core elements, and it is not rare to use them conjointly. Some illustrative examples are brief–strategic family therapy and multisystemic therapy, both of which incorporate representative elements from both approaches.

In general, literature has shown that systemic family therapy has a significant affect by reducing internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents, as well as improving overall family operation [35,36]. However, in spite of the evidence indicating gender differences in aligning problems, specially in internalizing symptoms, most available studies take not taken into account the boyish's gender when examining the impact of these interventions [49]. In addition, nearly studies have focused on individual outcomes or on family unit operation every bit a whole, rather than incorporating parent–kid dyadic measures or parental dyadic measures. Research has shown that some of these dyadic dimensions play an important office in families with adolescents with mental health bug; they should therefore exist incorporated in effectiveness evaluations. More specifically, coercive and permissive parenting practices [50,51,52] accept by and large been considered every bit 2 of the most important predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems. Other parenting dimensions linked to child psychopathology include: Depression sense of parental competence, defined equally the perception parents accept of their own performance as parents [52,53,54], and loftier levels of interparental conflict [55]. Equally a result, parental practices, sense of parental competence, and parenting brotherhood constitute intervention targets and should exist included in effectiveness evaluations.

For some of these dimensions, the studies available highlight the need to control gender differences. Specifically, there is evidence of important differences in parenting practices between mothers and fathers, with mothers scoring college in advice and control dimensions [56,57,58]. In addition, there is evidence of gender differences in the perception of parenting brotherhood and co-parenting; more than specifically, in parental back up and involvement dimensions. Thus, mothers are more probable to be involved in parental decision-making processes than fathers but also experience less supported in their parental role [59].

In this framework, the goal of this report was to evaluate the effectiveness of structural–strategic family unit therapy on dissimilar private, dyadic, and family dimensions in families with an adolescent with a mental health trouble; to do so, nosotros conducted a comprehensive analysis and incorporated a gender perspective. According to previous bear witness on systemic family therapy, we expected a reduction of internalizing and externalizing symptoms of adolescents, as well as an improvement in family operation. Due to their role in child psychopathology, a reduction of coercive and permissive parenting practices every bit well as an increase in sense of parental competence and parenting alliance were hypothesized. Because of an absenteeism of previous studies, we did not have expectations regarding the adolescent's gender, although higher improvements in mothers were expected in comparing to fathers.

2. Materials and Methods

ii.1. Study Design

This study was function of a wider research project assessing the effectiveness of a structural–strategic family therapy (SSFT) initiative run by mental health services in Southern Kingdom of spain (Andalusia) for families with an adolescent with a mental wellness problem. This initiative combined the theoretical principles and techniques of structural and strategic family therapy in order to reduce the adolescent's mental behavior problems and meliorate family relationships. The family therapy sessions initially focused on establishing a therapeutic alliance with all members of the family, providing them with a rubber, nonjudging space where all of them felt understood. Afterwards, the objectives of the sessions were to fix articulate boundaries betwixt the subsystems, to strengthen the parental subsystem encouraging joint decision-making and teamwork, to highlight and balance parental authorization with the increasing need for autonomy from the adolescent, and to reframe the relationships within the family system. Both the referred adolescent with a mental wellness diagnosis and his/her parents participated in SSFT; any other significant family unit members were also asked to attend. The intervention was led by two therapists trained in structural and strategic family therapy (a clinical psychologist and a psychiatrist). On average, the handling consisted of a 1-hr session each month over a period of approximately ten months [60].

For the purpose of the evaluation, a quasi-experimental design was followed, including a pre-test versus post-test evaluation of the participants of an experimental group (EG). This EG consisted of the population of families receiving the SSFT intervention during the study (i.due east., between 2009 and 2012).

ii.ii. Participants

The sample consisted of 41 participants (51.22% mothers, 48.78% fathers), whose adolescent children had been referred to mental health services in the Southward of Spain. The children's ages ranged between ten and 17 (1000 = fourteen.12, SD = 1.79), and in that location was a higher percentage of girls (73.17% girls and 26.83% boys). Most families were ii-parent (xc.24%), with almost all of them having four members (Yard = three.82, SD = 0.85) and an average of two children (1000 = 1.eighty, SD = 0.51).

Following ICD-ten criteria, behavioral disorders were the most common diagnoses (31.71%), followed past anxiety (29.27%), mood (17.07%), and eating disorders (17.07%). Other less frequent diagnoses included personality disorders (nine.76%), psychotic disorders (nine.76%), and pervasive developmental disorders (4.88%). Approximately twenty% of adolescents with ane type of disorder met the criteria for another class of disorder (19.51%), with half of the comorbidities between behavioral and anxiety disorders (9.76%) and the other half between anxiety and mood disorders (9.75%).

2.3. Measures

The study followed a multi-informant approach, collecting data from practitioners, caregivers, and target adolescents. In this newspaper, information provided past practitioners and caregivers is included. Practitioners provided data virtually boyish and family sociodemographic profiles. Caregivers informed almost the target boyish behavior, as well every bit near their parental sense of competence, parental practices, perceived parenting alliance, and perceived family unit functioning. These measures are described below.

Sociodemographic profile: Nosotros compiled an ad-hoc questionnaire to collect sociodemographic data about the target adolescent'due south age and gender (by measuring sex) and the family structure (one/2-parent structure) and composition (number of family members and children at home).

Kid behavior checklist for ages 6–18 [61]: This inventory provides information on kid and boyish behaviors from the perspective of caregivers. It measures both positive competences and problem behaviors (internalizing and externalizing). A compilation of 113 items (ranging from 0 = not true to two = very true or often truthful) measures internalizing (withdrawn/depressed, somatic complaints, and feet/depression) and externalizing problems (dominion-breaking and ambitious behavior). Cronbach's alpha coefficients were α = 0.85 for internalizing problems and α = 0.89 for externalizing problems. Higher scores indicate greater behavior problems. Hateful scores were computed.

Parental sense of competence [62]: This scale explores perceived competence every bit a parent. It consists of 16 items with responses on a half dozen-point calibration. Two subscales can exist computed, measuring efficacy and satisfaction in parenting. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were α = 0.75 for efficacy and α = 0.73 for satisfaction. For both subscales, hateful scores were computed, with higher scores indicating greater parental sense of competence.

Parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire [63]: This 32-item musical instrument consists of three scales measuring authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting. The authoritative items reverberate reasoning/induction, warmth and support, and democratic participation; the authoritarian items reflect exact hostility, physical coercion, and nonreasoning/punitive strategies; and the permissive items reverberate indulgence and failure to follow through. All items are answered on a v-point scale, with higher scores showing higher administrative/disciplinarian/permissive practices. Internal consistency in this study was α = 0.81 for administrative practices, α = 0.79 for authoritarian practices, and α = 0.64 for permissive practices. Mean scores were computed.

Parenting alliance inventory [64]: This 20-item scale assesses the degree of commitment and cooperation betwixt husband and wife in child rearing. For each item, parents answer on a 5-point calibration. The total score revealed α = 0.94 in this report. We used the mean score, with college scores indicating stronger back up between partners as parents.

Family unit cohesion and adaptability scale [65]. We used the FACES-III, which evaluates emotional bonding between family members, as well as the adjustability of the family system. It is ranked on a 5-point calibration. Different other versions, the scores assessed with FACES-III are interpreted in a linear style, and then the college the score, the greater the level of family cohesion and adaptability. Internal consistency in this research was α = 0.74 for cohesion and α = 0.56 for adaptability. Mean scores were computed.

ii.4. Process

Mental health practitioners referred the families for SSFT intervention. SSFT practitioners enrolled the families in SSFT if they met the following criteria: (1) A child under eighteen was being treated by the mental health service; (2) the referred kid met ICD-10 criteria for: Pervasive developmental disorders; behavioral and emotional disorders with an onset usually occurring in childhood and boyhood; neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders; and if the previous criteria were not met, the child had to run into the requisites for an eating disorder process or astringent mental illness; and (3) SSFT practitioners, based on their professional person criteria through the ascertainment and interviews with both the adolescent and the parents, considered that the child'due south symptomatology could be related with a family dysfunction (e.one thousand., the symptomatology was limited to the family context, parental disagreement or dysfunctional communication patterns) or that the family dynamic was either being impacted by the symptomatology or maintaining information technology (e.g., difficulties in adjusting to changes due to adolescence or parental practices not coherent with the adolescent period, frequent or persistent family conflicts). If the intervention criteria were met, SSFT practitioners enrolled the family unit in the trial if they had an adolescent fellow member (10 years or older).

Ii trained researchers, external to the SSFT, interviewed the caregivers and practitioners of each family unit and assessed the adolescents at the mental health service facilities. The pre-test was completed earlier the starting time SSFT session, and the post-test in the final session (for those families that had attended at least 3 intervention sessions). The average length of time betwixt pre- and mail service-test assessment was ten months, which corresponded approximately to the school year. Every informant participated in the study voluntarily, later signing an informed consent class in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The aims of the research project were explained, and all participants were assured that their anonymity would be protected. Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics commission of the Andalusian Health Services (lawmaking 22/0509). No monetary incentives were offered.

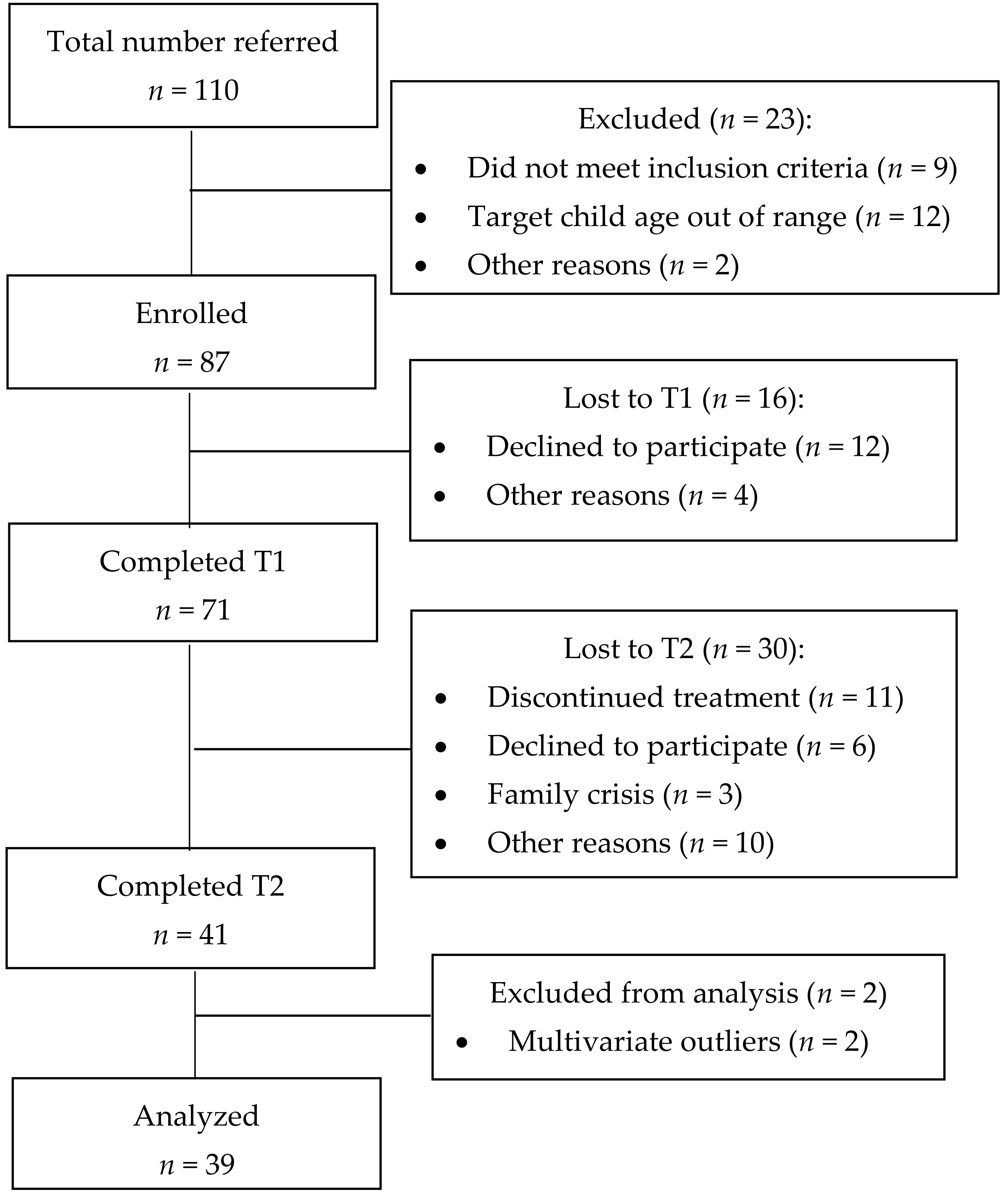

The flow of cases through the trial is shown in Figure i. Patients were classified as dropouts if they did not complete Fourth dimension 2 assessment protocols, despite existence contacted at least 3 times by the research team. The dropout rate at Time 2 was 42.25%.

Dropouts and completers were compared in all pretreatment variables using one-way ANOVAs for quantitative variables and Chi-square tests for qualitative ones. Partial eta squared and Cramer'due south V were computed equally consequence-size indices. Partial eta squared was considered small if <0.01, medium if ≥0.06 and <0.14, or big if >0.14; Cramer's V was considered small if <0.30, medium if >0.30 and <0.50, or loftier if >0.50 [66]. Meaning differences were not found in whatever variables, except for parenting brotherhood (see Table 1).

2.five. Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS v-eighteen (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) [67]. Missing data at detail level were extrapolated using the missing value analysis. When more than than 10% of the items from a questionnaire were missing, the instance was excluded from the corresponding analysis. If this were non the case, we then practical the SEM process to impute the information, having previously checked that the data were missing at random using Little's MCAR exam. We found less than v% of missing information with an MCAR distribution.

We examined univariate and multivariate outliers using box plots and Mahalanobis' altitude, respectively [68], finding 2 multivariate outliers which we excluded from subsequent analyses. Other statistical assumptions for parametric tests were checked and confirmed following Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black'due south [69] recommendations (i.e., linearity, normality, homogeneity, and absence of multicollinearity and singularity). As an exception, high kurtosis for parental alliance required a reflected and logarithmic transformation.

Nosotros based statistical conclusions on effect-size indices when statistical significance did not reach significance due to small sample size. Nosotros examined primary and interaction effects from mixed factorial ANOVAs for the analyses of effectiveness, because the pre-post measures as within the subjects' cistron (change) and informant's gender as betwixt the subjects' factor. Nosotros used partial eta squared equally an effect-size index, with the conventional limits of 0.01, 0.06, and 0.fourteen for the small, medium, and large levels of effect size, respectively [66].

3. Results

Outset of all, we examined the principal effect of gender and plant neither a meaning effect nor a medium or big consequence size. Equally Table ii shows, later controlling for gender, the modify between pre- and post-measures was significant for several dependent variables. Thus, the adolescents exhibited fewer internalizing and externalizing problems in the post-test with a loftier effect size. In turn, parents reported college satisfaction, as well as fewer disciplinarian and permissive practices, too with a loftier effect size. Moreover, college efficacy as a parent and more administrative practices were reported with a medium effect size. Finally, the interaction betwixt modify and gender was meaning for the parenting alliance variable, with a loftier effect size.

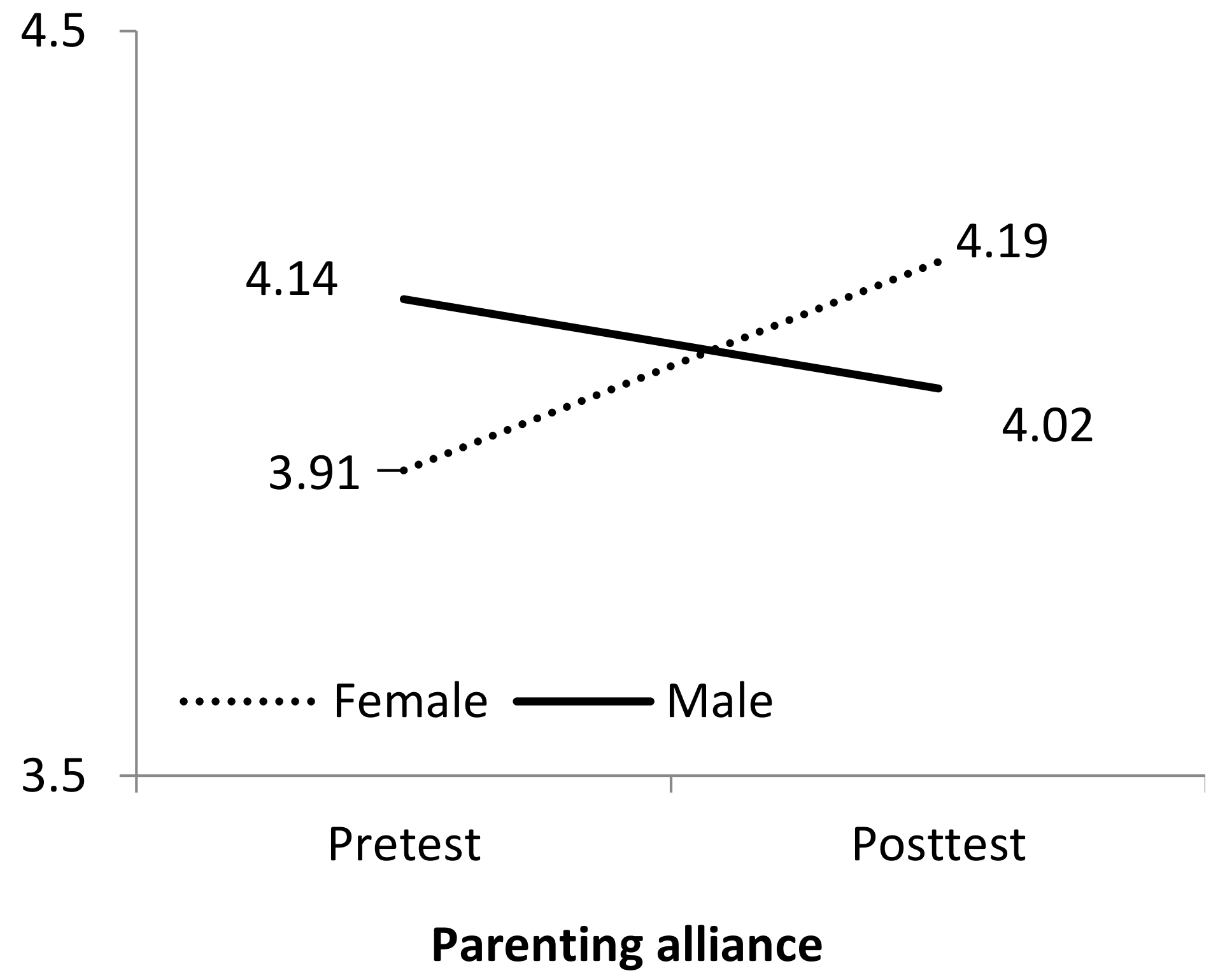

The change * gender interaction is plotted in Figure 2, and it shows that mothers improved their parenting brotherhood afterward intervention, while the reverse occurred with fathers. To investigate further into the interaction event, nosotros performed a simple repeated measures ANOVA for each gender. The results showed that mothers significantly improved their parenting alliance afterward treatment with a loftier issue size, F(1,18) = 4.54, p = 0.047, ηtwo partial = 0.20, but no statistical difference was observed for fathers, F(ane,xviii) = 0.24, p = 0.628, ηii partial = 0.01.

4. Discussion

The results of this study take shown a positive impact of a structural–strategic oriented family unit therapy on both the parents and adolescents in the family, dyadic, and private-level dimensions. The improvement observed subsequently the intervention was independent of the gender of both parents and adolescents, disallowment the parenting alliance variable.

The systemic arroyo understands the family equally a whole, not as a simple sum of individual members. Co-ordinate to this arroyo, a mutual objective in structural family therapy, regardless of clients' needs, consists of empowering and strengthening the family as a system, favoring the persistence of these changes over fourth dimension [38]. In consonance with previous empirical evidence [35,36], this study shows the impact of this approach in the family sphere, particularly in terms of improving family cohesion. This outcome is peculiarly relevant with vulnerable families facing difficulties associated with the readjustment of family roles and norms, response to new demands and needs of family unit members [ix,xiii,14]. This is the case of families with adolescents suffering from mental health problems, due to the existence of boosted needs, demands, and difficulties linked to the presence of the mental disorders [xv]. However, despite the importance of the abovementioned results, no improvement was observed in family unit adjustability. Families in this situation tend to behave inflexibly when negotiating and learning new means of resolving parent–adolescent conflict [42]. An improvement in family adaptability in this population would have been remarkable; the absence of changes in this dimension may exist due to reliability problems when assessing with FACES [70].

At a dyadic level, authoritative parental practices increased later on the treatment, and both authoritarian and permissive practices decreased. Only a handful of studies had previously assessed the effectiveness of a systemic family approach on families whose adolescents presented mental health problems in dyadic dimensions [44]. Parenting training in childrearing practices constitutes a cadre component of almost family interventions, particularly when child behavior problems exist [38]. Parental practices based on affect, dialogue, and reasoning are related to ameliorate family functioning [71] and adolescent adjustment [6,72,73].

The structural–strategic therapy tested in this study has also shown other dyadic effects. Participant mothers reported feeling more support from fathers in childrearing, although the reverse was non institute (fathers feeling more supported by mothers). This result is non surprising considering that mothers are usually involved more in childrearing than fathers and also feel less supported in their parenting office [59]. This divergence in gender may likewise be explained considering mothers reported a lower level of parenting alliance before the intervention, and therefore had greater telescopic for subsequent comeback compared to fathers.

At an individual level, participating parents reported better parental sense of competence subsequently the therapy. Thus, both fathers and mothers reported higher perceived efficacy and satisfaction as a parent. Again, this result is especially relevant equally parents from these families presented high levels of difficulty in exerting their parental role [15]. For example, there is evidence of the existence of additional parental stress on parents with adolescents presenting mental wellness bug, and the relationship between parental stress and less perceived efficacy and satisfaction as a parent [74]. Consequently, the increase observed in parental sense of competence could be mirrored past a decrease in parenting stress. In whatever event, the improvement in parental sense of competence is positive not only for parents at an individual level, but also for the adolescents and the family unit as a whole [53,75,76].

Finally, this written report has shown positive results in adolescent beliefs, regardless of gender [19,33,34]. The reduction in boyish problematic behavior both at external and internal level confirms the usefulness of structural–strategic therapy. This result tin can exist explained as a straight event of the intervention or equally an indirect effect of improvements in family performance [35,36], parental practices [fifty,51,52], parental sense of competence [52,54], and parenting alliance [55]. Every bit pointed out in the introduction, the absence of differences between boys and girls tin can be explained by the homogenization of adolescents' daily experiences in today's society [12].

This study has several limitations. First, a chief shortcoming is the small sample of families recruited in the written report. The loftier specialization and costs associated with SSFT together with the high-risk profile of these families aid to understand this limitation. The latter, due to mental health problems and family dysfunction, can also explain the high dropout rate reported in this study. Whatever the reason is, the statistical strength of the written report could be improved with a higher sample size, particularly if because the statistical conditions of the longitudinal analyses [77]. Second, we would take liked to have been able to deport a long-term assay to examine the persistence of treatment furnishings in the mid to long term. 3rd, the most important limitation of this study was the absenteeism of a comparison grouping to enable us to corroborate that changes between pre-test and post-test were due to the therapy and not to other circumstances [78].

5. Conclusions

Despite the abovementioned limitations, this study has fabricated some contributions. We drew on previous findings virtually the effectiveness of family unit-oriented and family unit-based interventions with adolescents with mental health difficulties [nineteen,20] from family unit systemic therapy approach [19,27,28,29,30,31]. While reaching the gold standard for effectiveness remains a afar goal for structural–strategic family therapy, this newspaper offers some evidences about its usefulness for improving private, dyadic, and family adjustment in families with adolescents with mental health difficulties [39].

In sum, this study has applied implications concerning the way specialized services for children and adolescents with mental health problems have been traditionally organized, and regarding the core elements that demand to be specifically targeted when working with these families. In general, specialized mental health services for children and adolescents have traditionally focused on symptom reduction and "parental preparation", which have proven to be useful and essential interventions. All the same, our results support the importance of incorporating complementary approaches targeting families every bit a whole in their regular services every bit to adequately address the complex needs and difficulties of families of adolescents with mental wellness issues [23]. In improver, this written report highlights the need to directly target certain core elements related to the dyadic parental human relationship and the parent–child relationship when intervening with families of adolescents with mental health bug. Finally, gender-related results support the idea of differentiated approaches when working at a dyadic parental level, such as co-parenting. Mothers and fathers seem to not only experience co-parenting differently but also reply differently to interventions that directly target this cadre chemical element [59]. Therefore, this study highlights the relevance of taking into account and incorporating gender-based strategies in interventions.

Author Contributions

Project administration, supervision and methodology: L.J., A.Fifty., and V.H. Data curation: S.B., L.J., and B.L. Resources: A.L. Conceptualization, formal analysis, and writing: L.J., V.H., B.L., and S.B. All authors take read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This report has been supported by the Research Project "Effectiveness of the family therapy handling developed in mental health services. Assay of effectiveness moderators". This piece of work was also supported by the Castilian Government (MINECO, Ministry building of Economics and Competitiveness). Project reference: EDU2013-41441-P. In addition, the Ministry of Educational activity, Civilization and Sports has funded the author S.B. with a predoctoral grant (FPU 014/6751).

Acknowledgments

To M.J. Blanco, coordinator in charge of the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Unit, Virgen Macarena Hospital (Seville, Spain), for her technical support in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of interest.

References

- Lawrence, D.; Hakefost, J.; Johnson, Southward.Due east.; Saw, S.; Buckingham, West.J.; Sawyer, M.G.; Ainley, J.; Zubrick, Southward.R. Key findings from the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2016, fifty, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, South.; Daral, Southward.; Sharma, S. Investing in our adolescents: Assertions of the 11th World Congress on Adolescent Wellness. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, nine–xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiteford, H.A.; Degenhardt, 50.; Rehm, J.; Baxter, A.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Charlson, F.J.; Norman, R.E.; Flaxman, A.D.; Johns, N.; et al. Global burden of disease owing to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Illness Report 2010. Lancet 2013, 382, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Home Page. Available online: http://world wide web.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 22 September 2018).

- Kieling, C.; Baker-Henningham, H.; Belfer, M.; Conti, M.; Ertem, I.; Omigbodun, O.; Rohde, L.A.; Srinath, Due south.; Ulkuer, N.; Rahman, A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. Lancet 2011, 378, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. The Handbook of Child and Boyish Clinical Psychology: A Contextual Approach, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-138-806009. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, G.B.; van der Ende, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Child and adolescent problems predict DSM-IV disorders in adulthood: A fourteen-year follow upwards of a Dutch epidemiological sample. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2002, 41, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentacosta, C.J.; Hyde, L.West.; Goodlett, B.D.; Shaw, D.S. Longitudinal prediction of disruptive beliefs disorders in adolescent males from multiple risk domains. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2013, 44, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, L. Adolescent development: Putting Europe on the map. In Handbook of Adolescent Development; Jackson, S., Goossens, L., Eds.; Psychology Printing: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-84169-200-five. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, M.E.; Compas, B.E.; Stuhlmacher, A.F.; Thurm, A.Due east.; McMahon, S.D.; Halpert, J.A. Stressors and kid and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of take chances. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, Thou.; Muzio, C.; Piccinini, Grand.; Flouri, East.; Ferrigno, G.; Pompili, M.; Girardi, P.; Amore, M. Life adversities and suicidal beliefs in young individuals: A systematic review. Eur. Kid Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 24, 1423–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannengrand-Willems, L.; Barbot, B. Challenges of adolescent psychology in the European identity context. In The Global Context for New Directions for Kid and Adolescent Development; Grigorenko, E.L., Ed.; Wiley Periodicals: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 69–76. ISBN 1520-3247. [Google Scholar]

- Lubenko, J.; Sebre, S. Longitudinal associations betwixt adolescent behaviour problems and perceived family human relationship. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworska, Due north.; MacQueen, G. Adolescence as a unique developmental catamenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015, twoscore, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A.; Antolín-Suárez, L.; Oliva, A. Support needs of families of adolescents with mental illness: A systematic mixed studies review. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 32, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doornbos, M.M. The 24-7-52 chore: Family unit caregiver for young adults with serious and persistent mental illness. J. Fam. Nurs. 2001, seven, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Fifty.; Stroul, B.; Friedman, R.; Mrazek-Rochester, P.; Friesen, B.; Pires, Due south.; Mayberg, Due south. Transforming mental health intendance for children and their families. Am. Psychol. 2005, sixty, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lila, M.; van Aken, M.; Musitu, G.; Buelga, S. Families and adolescents. In Handbook of Boyish Development; Jackson, S., Goossens, L., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, The states, 2006; pp. 154–174. ISBN 978-1-84169-200-5. [Google Scholar]

- Goorden, M.; Schawo, S.J.; Bouwmans-Frijters, C.A.M.; van der Schee, E.; Hendriks, V.M.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. The cost-effectiveness of family/family-based therapy for treatment of externalizing disorders, substance employ disorders and delinquency: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larner, K. Family unit therapy with children and adolescents (Editorial). Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2016, 37, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.H.; George, P.; Armstrong, Chiliad.I.; Lyman, D.R.; Dougherty, R.H.; Daniels, A.Southward.; Ghose, South.S.; Delphin-Rittmon, M.E. Behavioral direction for children and adolescents: Assessing the show. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamat, R. The parental couple human relationship in kid and adolescent mental health. Clin. Kid Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruche, U.G.; Draucker, C.; Alkhattab, H.; Knopf, A.; Mazurcyk, J. Interventions for family members of adolescents with disruptive beliefs disorders. J. Child Adolesc. Pyschiatr. Nurs. 2014, 27, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossum, S.; Handegård, B.H.; Martinussen, M.; Mørch, W.T. Psychosocial interventions for disruptive and aggressive behaviour in children and adolescents: A meta-assay. Eur. Kid Adolesc. Psychiatry 2008, 17, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebow, J.Fifty.; Stroud, C.B. Family therapy. In APA Handbook of Clinical Psychology: Applications and Methods; Norcross, J.C., VandenBos, Thousand.R., Freedheim, D.Thousand., Krishnamurthy, R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 327–349. ISBN 978-i-4338-2129-5. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bertalanffy, L. General Organization Theory: Foundations, Developments, Applications; Brazille: New York, NY, USA, 1968; ISBN 978-0807604533. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. Clinical views of family normality, health and dysfunction: From a deficit to a strengths perspective. In Normal Family Processes: Growing Multifariousness and Complexity; Walsh, F., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, United states, 2016; pp. 28–56. ISBN 978-1-4625-2548-five. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, S.A.; Christian, S.; Berkeljon, A.; Shadish, W.R. The effects of family unit therapies for adolescent delinquency and substance corruption: A meta-analysis. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2012, 38, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. The effectiveness of family therapy and systemic interventions for kid-focused problems. J. Fam. Ther. 2009, 31, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, D.; Boston, P. Practitioner review: The effectiveness of systemic family unit therapy for children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2002, 43, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedinger, 5.; Pinquart, M.; Teubert, D. Furnishings of systemic therapy on mental health of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Kid Adolesc. Psychol. 2017, 46, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, Grand.S.; Feaster, D.J.; Horigian, V.East.; Rohrbaugh, M.; Shoham, V.; Bachrach, Grand.; Miller, Grand.; Burlew, K.A.; Hodgkins, C.; Carrion, I.; et al. Brief Strategic Family Therapy versus treatment every bit usual: Results of a multisite randomized trial for substance using adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 79, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassells, C.; Carr, A.; Forrest, Chiliad.; Fry, J.; Beirne, F.; Casey, T.; Rooney, B. Positive systemic practice: A controlled trial of family therapy for adolescent emotional and behavioural problems in Ireland. J. Fam. Ther. 2015, 37, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, D.; Carr, A.; Sexton, T. The effectiveness of Functional Family Therapy in reducing boyish mental health risk and family unit adjustment difficulties in an Irish context. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retzlaff, R.; von Sydow, M.; Haun, M.West.; Schweitzer, J. The efficacy of systemic therapy for internalizing and other disorders of babyhood and boyhood: A systematic review of 38 randomized trials. Fam. Process 2013, 52, 619–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Sydow, K.; Retzlaff, R.; Beher, S.; Haun, Thou.W.; Schweitzer, J. The efficacy of systemic therapy for babyhood and adolescent externalizing disorders: A systematic review of 47 RCT. Fam. Process 2013, 52, 576–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Stouwe, T.; Asscher, J.J.; Stams, G.J.; Dekovic, Grand.; van der Laan, P.H. The effectiveness of Multisystemic Therapy (MST): A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, T. Functional Family Therapy in Clinical Practice: An Evidence-Based Treatment Model for Working with Troubled Adolescents; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-415-99691-4. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, A.; Greeno, C.1000.; Marcus, S.C.; Marcus, S.C.; Fusco, R.A.; Zimmerman, T.; Anderson, C. Effects of structural family therapy on child and maternal mental health symptomatology. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2013, 23, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, S. Families & Family Therapy; Harvard University Printing: Cambridge, MA, The states, 1974; ISBN 0_674-29236_7. [Google Scholar]

- Colapinto, J. Structural family therapy. In Family Counseling and Therapy, 3rd ed.; Horne, A., Ohlsen, Chiliad., Eds.; Peacock: Itasca, IL, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0875812762. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Thou.P. Terapia estructural. In Manual de Terapia Sistémica: Principios y Herramientas de Intervención; Moreno, A., Ed.; Editorial Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Spain, 2014; pp. 263–296. ISBN 978-84-330-2737-5. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik, J.; Rio, A.; Murray, E.; Cohen, R.; Scopetta, Thou.; Rivas-Vazquez, A.; Hervis, O.; Posada, Five.; Kurtines, W. Structural family versus psychodynamic child therapy for problematic Hispanic boys. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1989, 57, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkley, R.A.; Guevremont, D.C.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Fletcher, K.E. A comparison of three family therapy programs for treating family conflicts in adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1992, 60, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styczynski, L.Eastward.; Greenberg, L.D. Terapia estratégica. In Transmission de Terapia Sistémica: Principios y Herramientas de Intervención; Moreno, A., Ed.; Editorial Desclée de Brouwer: Bilbao, Kingdom of spain, 2014; pp. 377–412. ISBN 978-84-330-2737-five. [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik, J.; Schwartz, South.J.; Muir, J.A.; Chocolate-brown, C.H. Cursory Strategic Family Therapy: An intervention to reduce adolescent risk behavior. Couple Fam. Psychol. 2012, 1, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, Chiliad.S.; Horigian, V.Due east.; Szapocnik, J. Brief Strategic Family Therapy: An empirically-validated intervention for reducing adolescent behavior problems. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 2008, 57, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santisteban, D.A.; Perez-Vidal, A.; Coatsworth, J.D.; Kurtines, W.Grand.; Schwartz, S.J.; LaPerriere, A.; Szapocznik, J. Efficacy of Brief Strategic Family Therapy in modifying Hispanic adolescent beliefs problems and substance utilize. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.50.; Powlishta, Thou.Thousand.; White, K.J. An examination of gender differences in adolescent adjustment: The upshot of competence on gender role differences in symptoms of psychopathology. Sex Roles 2004, 50, 795–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enten, R.S.; Golan, M. Parenting styles and eating disorder pathology. Ambition 2009, 52, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.; Ludlow, A.; Wenar, C. Developmental Psychopathology: From Infancy through Adolescence, 6th ed.; McGraw Colina: New York, NY, U.s.a., 2012; ISBN 978-007713121-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, K.R.; Woolley, Yard.50. The relationship between maternal cocky-efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent preparation. Child Care Health Dev. 2005, 31, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, P.Thousand.; Karraker, M.H. Parenting self-efficacy among mothers of school-age children: Conceptualization, measurement, and correlates. Fam. Relat. 2000, 49, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.L.; Prinz, R.J. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and adjustment: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Mena, P. Parental relationships, self-esteem and depressive symptoms in young adults. Implications of interparental conflicts, coalition and triangulation. Univ. Psychol. 2014, xiii, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. In Interpersonal Evolution; Zukauskiene, R., Ed.; Routledge: London, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, 2017; pp. 225–235. ISBN 9781351153676. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B.; Collings, W.A. Parent-child relationships during adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Contextual Influences on Adolescent Development; Lerner, R.Thousand., Steinbergm, Fifty.D., Eds.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, United states of america, 2009; Volume two, pp. 3–42. ISBN 978-0-470-14922-5. [Google Scholar]

- MicKinney, C.; Renk, Thou. Differential parenting between mothers and fathers: Implications for late adolescents. J. Fam. Issues 2008, 29, 806–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, South.Eastward.; Gallegos, One thousand.I.; Jacobvitz, D.B.; Hazen, North.L. Coparenting dynamics: Mothers' and fathers' differential support and involvement. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 917–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, A.; Hidalgo, V.; Jiménez, L.; Lorence, B. Estilos relacionales en terapia familiar. Necesidades de apoyo para el proceso de intervención. Mosaico 2015, 60, 16–xxx. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Rescorla, L.A. The Manual for the ASEBA School-Historic period Forms & Profiles; Inquiry Center for Children, Youth, and Families: Burlington, VT, USA, 2001; ISBN 0938565737. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.; Mash, E.J. A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1989, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C.C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.F.; Hart, C.H. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). In Handbook of Family unit Measurement Techniques: Instruments and Index; Perlmutter, B.F., Touliatos, J., Holden, G.Due west., Eds.; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, Usa, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 319–321. ISBN 978-0803972506. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, R.R.; Bruner, J.F. Development of a Parenting Alliance Inventory. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1995, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.H.; Portner, J.; Lavee, Y. FACES III; University of Minnesota: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0805802832. [Google Scholar]

- IBM SPSS. IBM SPSS Statistics Base of operations 18; SPSS: Chicago, IL, United states of america, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnik, B.Thousand.; Fidell, 50.Southward. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0205849574. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, Westward.C. Multivariate Analysis, 5th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0138132637. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, L.; Lorence, B.; Hidalgo, V.; Menéndez, S. Gene assay of FACES (Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales) with families at psychosocial risk. Universitas Psychologica 2017, 16, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matejevic, M.; Jovanovic, D.; Lazarevic, V. Functionality of family relationships and parenting style in families of adolescents with substance abuse problems. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 128, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawk, Southward.T.; Hale, W.W.; Raaijmakers, Q.A.W.; Meeus, W. Adolescents' perceptions of privacy invasion in reaction to parental solicitation and control. J. Early Adolesc. 2008, 28, 583–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Ma, F.; Huang, H.; Guo, Ten.; Chen, C.; Xu, F. Parental monitoring, parent-boyish communication, and adolescents' trust in their parents in Communist china. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e134730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, L.; Kendall, S. Parenting self-efficacy, parenting stress and child behavior before and later a parenting programme. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2012, 13, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardelt, M.; Eccles, J.Due south. Effects of mothers' parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on innercity youth. J. Fam. Problems 2001, 22, 944–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, N.E.; Bush-league, K.R. Relationships betwixt parenting surround and children'south mental wellness amidst African American and European American mothers and children. J. Marriage Fam. 2001, 63, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, D.K.; Roy, A.; Aryal, S.; Hur, Chiliad.; Duan, N.; Normand, S.L.; Dark-brown, C.H.; Gibbons, R.D. Sample size determination for studies with repeated continuous outcomes. Psychiatr. Ann. 2008, 38, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Jensen, J.L.; Rodgers, R. The control group and meta-analysis. J. Methods Meas. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, three–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants through the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of participants through the report.

Effigy 2. Interaction result of gender on parenting alliance.

Figure 2. Interaction result of gender on parenting alliance.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics for completers and dropouts.

Tabular array ane. Baseline characteristics for completers and dropouts.

| Completers %/M | Dropouts %/M | Differences χ2/F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target adolescent | |||

| Girls | 73.17% | 56.67% | 2.11 |

| Historic period | 14.12 | 14.14 | 0.01 |

| Family unit | |||

| No. of family members | 3.82 | 4.04 | 0.83 |

| No. of children | 1.lxxx | 1.60 | i.86 |

| Two-parent structure | 90.24% | 81.48% | 1.09 |

| Behavior problems | |||

| Internalizing | 0.fifty | 0.52 | 0.04 |

| Externalizing | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.01 |

| Parental competence | |||

| Efficacy | 3.10 | 3.22 | 0.26 |

| Satisfaction | 3.77 | 3.88 | 0.32 |

| Parental practices | |||

| Authoritative | three.65 | 3.67 | 0.02 |

| Authoritarian | ane.84 | 1.83 | 0.02 |

| Permissive | 2.35 | 2.54 | 1.09 |

| Parenting alliance | iv.03 | 3.59 | v.21* ηii partial = 0.08 |

| Family unit functioning | |||

| Cohesion | 3.65 | 3.44 | 2.00 |

| Adjustability | 2.64 | 2.76 | 1.16 |

Tabular array 2. Descriptives and inferential statistics for alter and change * gender interaction of the mixed factorial ANOVAs for each dependent variable.

Table two. Descriptives and inferential statistics for alter and alter * gender interaction of the mixed factorial ANOVAs for each dependent variable.

| Descriptives One thousand (SD) | Change F (ηii partial) | Change × Gender F (η2 partial) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Test | Post-Test | |||

| Beliefs problems | ||||

| Internalizing | 0.48 (0.21) | 0.33 (0.19) | 14.74*** (0.38) | 0.02 (<0.01) |

| Externalizing | 0.55 (0.26) | 0.35 (0.21) | 20.72*** (0.46) | 0.47 (0.02) |

| Parental competence | ||||

| Efficacy | 3.fourteen (0.68) | iii.32 (0.64) | four.04* (0.10) | 0.88 (0.02) |

| Satisfaction | 3.76 (0.seventy) | 3.98 (0.81) | v.19* (0.fourteen) | 0.12 (<0.01) |

| Parental practices | ||||

| Authoritative | three.61 (0.50) | 3.75 (0.53) | 4.25* (0.11) | 0.21 (0.01) |

| Authoritarian | 1.84 (0.46) | 1.65 (0.twoscore) | 11.30** (0.25) | 0.23 (0.01) |

| Permissive | ii.31 (0.77) | 2.05 (0.56) | 5.44* (0.fourteen) | ii.08 (0.05) |

| Parenting alliance | 4.03 (054) | 4.11 (0.63) | 0.89 (0.02) | 2.94 (0.08) |

| Family functioning | ||||

| Cohesion | 3.62 (0.44) | iii.73 (0.45) | iii.26 (0.08) | 0.13 (<0.01) |

| Adaptability | 2.65 (0.42) | 2.73 (0.44) | 0.91 (0.03) | 0.39 (0.01) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed under the terms and weather of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/7/1255/htm

0 Response to "Stephen Halpert Marriage and Family Therapy Berkeley Ca"

Post a Comment